Luther's excommunication

Luther Distances Himself from the Papacy Because of constant attacks from the Roman Church, Luther was forced to shape his ideology into an autonomous theology. During the years 1520-1521 he worked on the three great works "Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation", "The Babylonian Captivity" and "The Freedom of the Christian Man", thereby emotionally cutting himself off from Rome.

The inquisition against Luther was taken up again in 1520, partly because of these works. The peak of the inquisition came on June 15, 1520, with the Papal Bull of excommunication in which Luther was ordered to recant his teachings.

Luther reacted in protest. He burned the Papal Bull ("Exurge Domine") along with the book of church law and many other books by his enemies on December 10, 1520 in Wittenberg where the Luther Oak (Luthereiche) stands today. He is said to have yelled: "Because you, godless book, have grieved or shamed the holiness of the Father, be saddened and consumed by the eternal flames of Hell". This behavior caused a conclusive and irrevocable break with Rome.

On January 3, 1521 the Pope excommunicated Luther. The Emperor, however, felt forced to accept Luther because of the pro-Luther mood in the empire and because of the influence of various princes who were hoping to weaken the Pope's political influence through Luther. As a result, the rebel was guaranteed safe escort on his trip to the Imperial Diet of Worms.

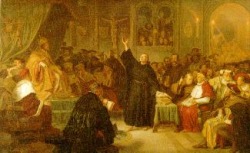

The Imperial Diet of Worms

Luther, who through the church's excommunication was practically declared a heretic, was invited to Worms by the Emperor who had been pressured by a few princes. Both the church and Emperor wanted Luther to recant his teachings while he was there. The princes who supported Luther hoped that through the forthcoming events the political power of Rome over Germany would be weakend.

Luther's powerful sovereign, Elector Friedrich the Wise of Saxon demanded that Luther not be outlawed and imprisoned without a hearing. Luther began his trip to Worms on April 2, 1521. The journey to the Imperial Diet did not embody the repentance the church had hoped for. The journey to Worms was more like a victory march; Luther was welcomed enthusiastically in all of the towns he went through.

He preached in Erfurt, Gotha and Eisenach. He arrived in Worms on April 16 and was also cheered and welcomed by the people.

Luther's appearance at the Imperial Diet was described as objective, clever and well thought out. He had to appear before the Emperor twice; each time he was clearly told to take back his teachings. Luther didn't see any proof against his theses or views which would move him to recant: "Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason - I do not accept the authority of the popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other - my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. God help me. Amen."

After he left the negotiations room, he said "I am finished." And he was for the time finished; Luther was dismissed, and not arrested because he had a letter of safe conduct (Schutzbrief) which guaranteed him 21 days of safe travel through the land. He headed home on April 25.

When Luther and the princes who supported him left Worms, the emperor imposed an Imperial Act (Wormser Edikt): Luther is declared an outlaw (he may be killed by anyone without threat of punishment).

On the trip home, Elector Friedrich the Wise allowed Luther to be kidnapped on May 4 (Luther knew about it beforehand). This took place on the one hand to guarantee Luther's safety and on the other hand to let him disappear from the scene for a short while; there were even rumors of Luther's death. This action also helped the Elector not to endanger himself because he could have been held liable for protecting an outlaw and heretic. Luther was taken to the secluded Wartburg and the Reformation had time to stabilize and strengthen itself.

Luther at the Wartburg and the translation of the New Testament

On May 4, 1521 Elector Friedrich the Wise allowed Luther to be brought to the Wartburg near Eisenach. The powerful Elector hoped that taking Luther out of the limelight would weaken the constant attacks against the Reformation. Luther lived incognito at the Wartburg; he called himself Junker Jörg (Knight George) and "grew his hair and a beard." Luther suffered from the exile "in the empire of outlaws" and complained of various physical ailments. In addition the many fights with Satan, recounted both by himself and friends, like the proverbial Throwing of the Inkwell must have been difficult times for him to work through...

Luther devoted himself to a new task. He translated the New Testament from its original Greek into German within eleven weeks; the work was later edited by Melanchthon and other specialists and printed in 1522. This so-called "September Testament" was tremendously popular in Protestant areas and as a result made a large contribution to the development of a standardized written German-language. Later, parts of the Old Testament were also translated. In 1534, a complete German language Bible was printed and also had a large circulation. Reformation theories were put into practice in Wittenberg which had become the center of the Reformation. In protest, three priests married in 1521 and the worship service was also altered. Luther watched these changes favorably from a distance, however, he stayed in close contact with his supporters in Wittenberg through letters. It is important to emphasize the influence of Philipp Melanchthon and his work "Loci communes" (1521) which was the first formulation of Luther's teachings and was also a foundation for the theological works of the Reformation. In 1522, Luther returned to Wittenberg when the more radical functions of the Reformation appeared to have gained control (such as the iconoclastic movement under Andreas Bodenstein, aka Karlstadt).

Luther's return to Wittenburg and the Pheasants War

After the first iconoclastic movement in Wittenberg, Luther returned from exile. He even annulled some of the reformatory changes that he saw as dangerous because they would force people into a new belief which he did not want to do. Luther returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1521 and with his 'fasting sermons' brought the Reformation movement fwhich he thought had gotten too radical back to his moderate line. The outlaw's return was dangerous, but the reformers achieved partial success as far as Luther's safety was concerned: the Second Imperial Diet of Nuremburg declared the banishment of Luther as unenforceable. In 1524, however, at the Third Imperial Diet of Nuremburg the banishment was renewed, but the Reformation had rooted itself so deeply by then, that it seemed unlikely that Luther would be arrested. In the years that followed, Luther concentrated on spreading his beliefs through writings and sermons. In the work Of the Worldly Authorities, and How Much Obedience one owes Them Luther formulated the basis for his political ethics. Luther's moderate outlook comes to the foreground once again. From 1522-1524 Luther's preaching duties receive priority; he went on preaching trips throughout central Germany and during the fall of 1522 even preached in Erfurt and Weimar. Luther felt it was important to proclaim and illuminate the Gospel to the people.

With his writings On the Order of Worship and Formula missae Luther carried out his reforms in the worship service.

Once again the Reformation found new enemies, this time radicals within its own ranks, called Swarmers and Mobbing Spirits by Luther. Thomas Münzer, priest and former follower of Luther became a leader of peasant uprisings in Central Germany in 1525 which had already flared up in southwest Germany in 1524. The peasants, who called on the power of Luther's teachings, demanded more just (economical) conditions, even if that meant the downfall of the authorities. In his sermons, which he also held in the areas of unrest, Luther stood firm against using force; he only received refusals from the peasants who had hoped for his support. Luther nevertheless encouraged them to free themselves from the spiritual despotism of the authorities not from their economic or political influence. From these experiences came the desolate work "Against the Murderous and Thieving Hordes of Peasants", which is still a controversial work. The peasants were defeated on May 15 at the battle of Frankenhausen.

Luther's marrige

On June 13, 1525 Luther married Katharina von Bora, a nun who had fled from a convent in Nimbsch, near Grimma, and had taken refuge in Wittenberg. Luther's marriage to Katharina (who was 16 years younger than Luther) was oppposed by many of his friends who saw in it the downfall of the Reformation. Philipp Melanchthon spoke of it as an "unlucky deed". He did not know anything about Luther's plan and was not invited to the wedding.

Katharina took over the household, particularly the household expenses; it is said that Dr. Luther did not have a clue how to run a household. She also proved herself to be a good housewife and gardener.

Luther's household included not only his wife and six children, but also one of Katharina's relatives and after 1529 six of Luther's sister's children. Luther also housed students in his home to help the family's financial situation.